In the fall of 2008, I played a show at Bard College with a band whose performance has since stuck in the corner of my brain like a piece of Doublemint on the bottom of a Burger King booth. Any details of the set that night have long slipped from my memory—I might’ve been stoned—but I can still recall the faint outline of a two-piece freakout unit whose music and performance style seemed adjacent to the noise rock of the time but also on its own tip entirely. I remember a mangled whimsy.

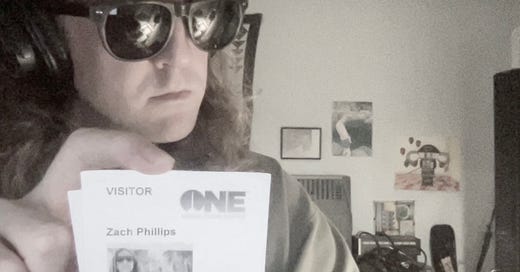

Flash forward 15 years later: A chance meeting with Zach Phillips at a reading in Brooklyn led to the revelation that the band I played with at Bard was called Heat Wilson and that Phillips was its drummer. Since that show, he has gone on to work on plenty of great “underground music” projects I have been aware of, including the duo Blanche Blanche Blanche and the label OSR Tapes. Over the past few years, the thing that has taken up a lot of his energy is Fievel Is Glauque, a band he leads alongside the Brussels-based singer Ma Clément.

Fievel Is Glauque’s brand of wonky, jazzy pop is driven by their harmonic sensibility and musical interplay more than any specific record collector inputs. The band has received some rightful acclaim: They put out their new record, Rong Weicknes, on Fat Possum, and Stereolab took them on tour a few years ago. It’s a complicated world out there, but it’s nice to see some real heads putting a few W’s on the board. Recently, Zach and I had dinner together at Bedouin Tent in Boerum Hill.

I'm sure this meal is going to be great.

It's going to be really great for me because the last thing I ate was like 20 hours ago.

Oh, shit.

I don't know why I do that to myself. I do make coffee with alt milk in it, because I can't drink milk.

Are you working on music right now?

Yeah.

Is that a part of why you're not eating?

I mean, I do eat. I have such a weird schedule. And yeah, the weird schedule is worsened by working on music, because I like to work really, really late at night. I like to start working on music around midnight or one and I'll go until eight or nine and then I'll sleep until three or four. That's just recently, though. I'm discovering that it works. I think the next step is to move out to the country and become one of those people who goes to bed at nine and wakes up at three or four, and is there for the dawn and the quiet hours.

So New York is bringing out this schedule?

Yeah, I feel a little bit like I’m resisting. I’m trying to feel the environment differently. In those small hours of the night, you hear insects, you hear the birds start to stir. There are bite-sized doses of humanity. You might see somebody in their window. An AC unit turns on. The wind rustles through the trees and then you start to see the light start to peek out. And you're like, Okay, this really is an environment. It's not dominated by people. People are just a feature of it. But then in the day that feeling sometimes gets lost. People are so magnetic. The energy of everybody walking around, everything people are putting out there, it's a lot to contend with. Broadway Junction.

Is that where your studio is?

No, but I was just there. Studio-wise I just have a room in my apartment with a piano and a few tape machines that I haven't used in a long time.

Are these sketches to bring to an ensemble later?

For the last three years, me and Ma will occasionally take something I've written on my own and use it for Fievel, but really as a rule since 2021, we've written everything together in person. And that's been really cool, and it feels different from writing on my own. But as a consequence of that, for a while I took the longest break from writing and recording on my own that I ever have since I was 17. Recently I was like, I gotta do something. So I just wrote a song one night, opened Audacity and started recording with the laptop mic. I had the window open, and there was a lot of environmental sound getting into the recording. It was really late, so I had the practice mute on the piano and the soft pedal, and the computer sitting on top of the piano, so it's getting a lot of muddy stuff in it. I was like, actually that sounds pretty cool. I made a whole album like that, and I just finished it.

And what name is that going under?

Oh, just my name. But I don't know when I'll release it or what the deal is with that. For me, finishing something is like a gesture, it's like a magic invocation. And if you send it to a couple friends, then you know it's kind of fixed.

That's a good attitude to have. For me, I'm going to keep fucking with it even after it's at the mastering place, I will freak out.

No shit.

I'm not defending myself here.

I mean, the grass is always greener. So many great musicians are tinkering, and I'm just not like that at all. Or maybe I am, but the tinkering is hidden. One thing I like to think about is I’m 36 years old, I’ve been doing this for a little under 20 years. I'm just starting.

I think there is something about the music you've been making recently with the band—you might have the ability to age with it. I think about the music I've made in my life and it feels so tethered to youth.

I admired your flow. It was very calisthenic when I was going to see you play. You moved, you know?

Yeah, I guess even the way I performed was very youthful.

Look at Iggy Pop, though.

It's true.

I came out of noise, tape collage, musique concrète, and listening to a lot of stuff that felt like it had some loose hairs or experiments involved, whether it was just stuff that got recorded wrong, or things created by miscreants and perverts, people who are lost to the world, people who are rebels where you're not quite sure what they're rebelling against, and you get the sense that they aren’t totally sure either, but it doesn't detract from the potency of their rebellion.

In noise, it almost felt like they were rebelling against these other forms of counterculture.

The second that a group constitutes itself, there is a need for some kind of rebellion, which is silly, too, and that's another reason why noise can be so great—the silliness of it. Silliness couched in seriousness, couched in yet more silliness, couched in, like, violent anger, couched in total levity and compassion and kindness. My entry to underground music was in Western Mass, I was enthralled with what people like Chris Cooper, Jess Goddard, and id m theft able were doing, and my entire frame was deconstructionist, I was more focused on conceptual lyrical poetry than any music. Songwriting mostly seemed impossible, something from the past, and then finally I met these charismatic songwriters the Weisman brothers and Ruth Garbus, who weren’t using extended techniques with their instruments, instead the extended technique was more like I'm going to freak myself out and freak you out with harmony, and I sort of was like, Wow, I want to learn how to do that. It's taken a long, long time and just a lot of writing to get to a point where I have a relationship with harmony where that's not even what’s centrally interesting anymore.

Yeah, there’s a lot of harmonic sophistication happening on these Fievel records. Did you study? There's some people in the underground who have these secret tricks in their back pocket and it takes a second to bring them out. Were you a jazz kid growing up?

No, I was a weird, sad, upset kid. I was into video games. I became a huge music nerd because I heard “Paint It Black,” and then all these movie soundtracks really helped me—like the soundtrack to Dumb and Dumber, The Butthole Surfers are on it doing “Hurdy Gurdy Man.” I asked my parents if I could take bass lessons because I heard “Hurdy Gurdy Man.”

Wow.

So I did that a tiny bit. I took classical piano lessons, honestly, to please my mom. And I had a knack for it, but I refused to learn any theory because I was antagonistic. From age 8, I was saying the thing that a lot of people say about theory, which is, like, I don't want it to affect my creativity, and then I realized I needed it when I was 17 and I wanted to play, like, T. Rex songs on the piano and I couldn't figure them out.

What was the name of your band that played with me at Bard in 2008?

I think that was Heat Wilson. I would have been playing drums. That was almost a noise rock band.

I remember being really into it. I was probably 21 or 22. So you must have been 19 or 20.

Right. So the age difference was immense.

There is that thing where the DIY generation that's a few years above you feels like a major gap.

Yeah. It's huge.

Once you hit your late 20s, then the years go by fast.

You rapidly learn the difference is kind of imaginary.

I remember being 23 or 24 and feeling like, Oh shit, I better make something great. My time is ticking.

I know.

But that’s a regret. Maturity happens slower now than it did in previous American generations. It’s much more common now for people in music to have a breakthrough moment later in life. That used to be a little more atypical. Guided By Voices were in their mid 30s when they blew up and that was almost like a novelty in the 90s. I'm sure when people write about you, they're not remarking on your age necessarily.

No, and I remember being younger and thinking that as you age in art and especially in music, it necessarily starts to be like, I don't know, late-period Steve Miller or something. Suddenly, all of your records are hot trash, and not in an interesting way. I've since learned that that's not true at all. I think people get better. And it's almost like, if you aren't getting better, then what are you doing?

Do you feel like Fievel is the most actualized articulation of something you’ve been kind of dancing around for a while?

I've had a few really close collaborative things over the years. I would say the first really, really deep thing was my band Blanche Blanche Blanche. Fievel at this point has gone deeper, Ma and I have, partially because Blanche was very contextual and Sarah became very clear early on—she was like, Look, yeah, I'm down to consider things like tours or doing an interview if it's fun, when it's fun, when it's convenient, but this is not my goal. She was like, I don't want to be a professional musician, I don't want to be a professional artist, I just want to use this stuff for joy in my life, I want to have fun but I have limits. And that was hard for me because as people started to rally behind Blanche, I got really excited. And I was like, Oh my god, maybe I could actually do this stuff.

You could go to Milwaukee.

I could go play a show in Milwaukee! At that time, too, the prospect of getting $10,000 from a label or something, living in Brattleboro, Vermont, that would mean my rent and studio space was paid for for like two and a half years.

Yeah, for sure. But then there's the things that come along with that.

I went into biting the hand that feeds me pretty quick. Sarah would just ignore that hand because she didn't recognize it to be holding food. Which was correct. And then I had another very close partnership that ended under difficult circumstances. I resigned myself to kind of, I'm just going to make little tapes for the rest of my life, when I want to, and I almost hope nobody checks them out. I want to be left alone. I want to keep the scale as small as possible. You know, keep it super bounded. And then Fievel accidentally started.

I was thinking of it totally in that way, I was not ambitious about it. And Ma certainly wasn't ambitious about it. This is her first real band. There's been a million conversations like, Do we want to open that door? Getting offered the tour with Stereolab was a big moment—this is going to be really, really hard, and it's going to mean that we change the scale that we work on, and it's going to necessitate getting help, and learning how to accept help. Learning how to not do everything ourselves, which is still challenging. We're still warming up to that.

So anyway, the question was, like, is this the most fully realized thing or something? My instinctive answer is no. Everything's been realized the whole time to the same extent. What's different about this is that for reasons beyond me, people responded to this band. It might be because it's good. It might be because we made a series of decisions that happened to be strategically really smart, although we had no sense of strategy in making those decisions. Our first record was recorded with a $50 Samson mic on a little mono Marantz machine, not even one of the nice ones. It was recorded at rehearsal. The reason we put that out first, well, we really liked it, but we also had studio recordings of 65 songs by then.

That’s crazy.

Those rehearsals were leading up to five albums worth of studio recorded stuff. And basically I just, I had never mixed on the computer, and I didn't know how. These mono things that can't really be edited—let’s just get that out there. And then we released it on New Year's Day, and for some reason it caught on more than anything else I’ve ever done.

I think it's one of those things, too, where you spend a lot of time working, and you get good, then all bets are off.

Right.

But, yeah, I'm curious about that sort of scalability. When you go out with Stereolab or something, I assume you're going to have to put together an ensemble.

Yeah, there were six of us. We slept in a hotel one time in 40, 43 days or something like that. We got a hotel in Fargo.

So this was straight DIY accommodations?

Yeah. We rented a van. The cost of the van rental and gas was already several grand over our guarantees. I was putting up the majority of this money. I'm used to that—I'm used to, whatever I got, I'll wager it on this thing. But I think it was right at that moment where that started to cause more friction for me.

You’re getting older.

Man, if this tour doesn’t work out, you and your girlfriend are going to have to find a room to share in somebody’s else’s apartment instead of having a place together. It was that kind of thing. Stressful. But yeah, it was very DIY. We brought some air mattresses, which ended up being really helpful. We were playing a thousand people in the audience kind of gigs and we would get on the mic and be like, By the way, if anybody has a place we can crash, come to the merch table.

Blanche Blanche Blanche definitely had a footprint. But hearing you talk about it, you weren't a deep touring band, though you could have probably been.

I'm so bad at touring. I remember very well we played a Blanche show in Louisville and it was snowing. We were touring with Guerilla Toss and somebody said, “That was the worst band I've ever seen” about us. And I was strangely proud.

The more you go out in the world, the more you're going to get that.

Right.

I would sometimes get asked to go on support tours and it was always an interesting experience. I would assume Stereolab has a fairly cool crowd, but some indie rock tours, you're playing for people that are close-minded in a way that can be difficult to puncture. Craft beer dads, that kind of thing.

It’s not anything essential about the audiences. It's partially the environment sponsored by the whole system. They've already been gouged on Live Nation or whatever for their tickets. They show up, they left work a few hours ago. They have to wait in line. There's some new wristband system that's electronic. They're scanning their social security card or something. And the whole thing is built to create an environment where you're almost pitted against each other.

On the surface, your band almost feels like some really informed, record collector shit. But then reading interviews with you, that doesn't actually seem to be the case. You’re not really a pastiche band, in the way that Stereolab or Beck might’ve been—people that are really intentionally collaging source material.

No, we're not doing that. And I know people whose music I admire, whose whole project is like, I go through huge amounts of listening, I identify things I like, and then I try to take elements from this thing. Well, I don't really believe what I or anybody else has to say, accounting for where stuff comes from exactly, because it all has the shape of an alibi. The truth is that my inspiration comes from the harmonic language of the piano, and from the processes that get created by habit and happenstance and experimentation to give us something to do, to set limitations, so that it doesn't become this thing of, let's make something we really like, which I've always found to be totally desiccated.

The most lifeless approach to making art, in my opinion, is let me try to get something I really like going. I freeze, I become paralyzed, I have nothing to show. I emphatically don't want to try to make an argument. I worked in the law for a long time, civil rights law, and in that, you're always thinking about, like, how can I make this fact pattern speak so that I can make a narrative argument? That's a great kind of process, and it has its own lessons, but if I'm writing alone or with somebody else, the second I identify something that reminds me of a conscious argument or someone else’s song, pretty much that song is canceled, or at least that part is going to change. Sometimes I'll bear it out because you're in that kind of mood, but I just don't feel it that way.

I love music, and I do study music, and some of the music that I've studied, I can see how it's in the work, like specifically a lot of Uruguayan music. I'm not a record collector, I'm a Soulseek kind of guy. I like physical media, but I like music more. I've noticed all kinds of things popping up. I've noticed that because basically delivering food and listening to every Wu-Tang solo album at least 2,000 fucking times, the syllable counts and rhythmic patterns of some of the flows, specifically the Raekwon, Ghostface, GZA stuff—I remember checking Blanche lyrics before and being like, what does that syllable feel remind me of, and then I'm like, that's straight up from this Raekwon song or something.

Amazing.

There's stuff to find everywhere. Currently, yeah, some of the harmonic language in some of this new Fievel music does seem to be, I can smell Uruguayan music that I love. I don’t know, I really wish there was another model for thinking about things than the make a witch’s stew out of a lot of influences and boil them into a substrate, and that's supposed to be the essence of your sound. It used to really bother me that it was the only logic.

It's the logic of our era because we have so much access. It's cool to hear you say that, though. It's always been a hard thing for me to transcend that thinking. I'm very much a product of my time—and I don't have the musical training.

Well, I don't either. I don't. I've been trained by the band. If you want to get better at whatever instrument, try to get people together who play better than you and try to communicate your ideas to them, and they're going to say shit to you, like, I have no idea what you're talking about. And then you're like, Well, how would you explain that? They're like, Like this. And you start doing that, but you do it slightly wrong, and they're like, That's cool that you did that kind of wrong. And then you're like, Oh, I guess I have some unique ideas.

Really studied players playing with more naive players often delivers good results. I think about The Velvet Underground as being such a classic example of that magic.

I've been thinking about Lou a lot recently, because lyrics are a big deal to me, and the way he uses rhyme and uses non-rhyme and just his attitude throughout. Throughout all these different eras. A big one for me is “My House” from The Blue Mask. It's just amazing all the different things that can happen. Everything is double-edged.

Yeah.

Instrumental skill is not at all at the center of why things are beautiful. It can help. A lot of things can help. Inattention can help. Attention can help. The things that I count as influences are things that have changed the way I look at things, changed the way I hear things and feel things. It's not just in the music, it's in how people relate to the music. Royal Trux is a big one—a kind of phenomenological approach to being oppositional, let's say. Or Maher Shalal Hash Baz is this group from Japan. Everything Tori Kudo’s had to say about where that music is coming from and where it's going. There's a lot of things like this, you know, people who dare to not be sure and to do more than they can intend to, and it's never just a product, whatever it is. It could be Bieber. It's never just a product.

No.

It's a whole life, every little song. It's a whole life.

Rong Weicknes is out now. Fievel Is Glauque on Bandcamp and Instagram